ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31679

THEORIES AND COUNTERHEGEMONIC EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES. ABOUT DISRUPTIVE PEDAGOGY

Teorías y prácticas educativas contrahegemónicas. Sobre la Pedagogía disruptiva

Blas GONZÁLEZ-ALBA*, Moisés MAÑAS-OLMO*, María Esther PRADOS-MEGÍAS** and María SÁNCHEZ-SÁNCHEZ**

*Universidad de Málaga. España.

**Universidad de Almería. España.

blas@uma.es; moises@uma.es; eprados@ual.es; Gabbers1983@hotmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4769-6522; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7286-4786; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6413-2219; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9746-9697

Date received: 25/09/2023

Date accepted: 11/12/2023

Online publication date: 01/07/2024

How to cite this article / Cómo citar este artículo: González-Alba, B., Mañas-Olmo, M., Prados-Megías, M. E. & Sánchez-Sánchez, M. (2024). Theories and Counterhegemonic Educational Practices. About Disruptive Pedagogy [Teorías y prácticas educativas contrahegemónicas. Sobre la Pedagogía disruptiva]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 36(2), early access, e31679. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31679

ABSTRACT

The concept of pedagogical disruption has been related for years with pedagogical innovation, the break with traditional educational models, the use of ICT and the search for educational quality; even so, this concept, from a practical sense, is poorly defined so it is still an element of study, even more so when we refer to secondary education. In this research we present and analyse 47 pedagogical practices developed in secondary schools that respond to the principles of disruptive pedagogies, both nationally and internationally. A systematic review of the literature is carried out using different databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, Jábega Catalogue, Dialnet). The results show, on the one hand, that pedagogical disruption can be used as a valuable tool to improve aspects of the quality of traditional education, especially in contexts where social transformation is required. On the other hand, it provides a set of strategies with which students feel more motivated and committed to their learning, obtaining better academic results.

Keywords: pedagogical innovation; pedagogical experience; high school; systematic literature review; disruptive pedagogy.

RESUMEN

El concepto disrupción pedagógica se ha relacionado durante años con la innovación pedagógica, la ruptura con modelos educativos tradicionales, el uso de las TIC y la búsqueda de la calidad educativa; aun así, dicho concepto, desde un sentido práctico, está poco definido, por lo que sigue siendo elemento de estudio, más aún cuando nos referimos a la enseñanza secundaria. En esta investigación presentamos y analizamos 47 prácticas pedagógicas desarrolladas en centros educativos de secundaria tanto de ámbito nacional como internacional que responden a los principios de las pedagogías disruptivas. Se desarrolla una revisión sistemática de la literatura considerando la información recogida en diferentes bases de datos (Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, Catálogo Jábega, Dialnet). Los resultados muestran, por un lado, que la disrupción pedagógica puede utilizarse como una valiosa herramienta para mejorar aspectos sobre la calidad de la educación tradicional, especialmente en contextos donde se requiere una transformación social. Por otro lado, aporta un conjunto de estrategias con las que el alumnado se siente más motivado y comprometido con su aprendizaje a la par que le permite obtener mejores resultados académicos.

Palabras clave: innovación pedagógica; práctica pedagógica; enseñanza secundaria; revisión sistemática de la literatura; pedagogía disruptiva.

1. INTRODUCTION

This work is part of one of the actions promoted in two interconnected research projects. On the one hand, the national R+D+i project “Nomads of Knowledge: Analysis of Disruptive Pedagogical Practices in Secondary Education” funded by the State Research Agency in the 2018 Call for R+D Projects for Knowledge Generation and RETOS R+D+i Projects, with the code RTI2018-097144-B-I00. On the other hand, the project titled “Knowmadic Knowledge and Disruptive Pedagogical Practices: Emerging Community Narratives in Secondary Education”, funded by the Regional Ministry of Economy, Knowledge, Business and University within the framework of the FEDER Andalusia 2014-2020 operational programme, with the code UMA20-FEDERJA-121.

Following some of the results of both projects, we must consider that the present research focuses on disruptive educational practices that do not use technology and that are developed in secondary education. In this regard, we must consider that the concept of “disruptive” is not new in the field of education, since in the Anglo-Saxon sphere, disruption is associated with breaking the established order and challenging the hegemonic through the transgression of structures and rules of educational organisation. Currently, the term disruptive is associated with practices related to innovation, and in this context, terms such as disruptive innovation (Al-Imarah and Shields, 2019), disruptive pedagogy (Hedberg, 2011; Ocaña-Fernández et al., 2020; Ortega and Llach, 2016; Vratulis et al., 2011) and disruptive education (Abreu and Lorenzo, 2020; Eyzaguirre, 2022) have emerged. At first, disruptiveness takes on a multi-conceptual meaning in relation to the industrial, financial, and technological spheres, appropriating terms such as disruptive technology (Bower and Christensen, 1995) and disruptive innovation (Christensen and Raynor, 2003). Since the publication of the book The Disruptive Classroom: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns by Christensen et al. (2008), these terms have been treated from other conceptualisations.

According to this author, the term disruptive innovation should be considered in relation to educational practices that use technology and are open to other frames of reference that consider new needs, uses and values on an ongoing basis and with a forward-looking vision, anticipating socio-educational realities, situations and problems that challenge the hegemonic educational model and break with traditional educational models and practices (Christensen, 1997; Christensen et al., 2006). In this sense, to speak of disruptive innovation is to question the traditional paradigm and to consider the disruptiveness as a process (McDonald et al., 2017) that is transformative rather than punitive (Christensen et al., 2008; Christensen, 1997) and that develops at the individual, collective, community and institutional levels (Quilty, 2017). This way of considering the disruptiveness implies using other counter-hegemonic logics, as disruptive innovation aims to consider other people, groups, and needs that are not usually addressed in the educational sphere. This involves changing the way of thinking and doing, i.e. transforming existing approaches and practices with the intention of creating more effective and relevant solutions. However, educational transformations imply challenges that require significant investments in technology, staff training, and development of new educational materials (Fullan, 2007), without which implementation and sustainability would be complex. Authors such as Christensen et al. (2008) suggest that one limitation is the need to balance innovation and educational quality, since when adopting disruptive approaches there is a risk of identifying educational quality with academic results and, therefore, considering it solely in terms of standards or rankings, hence, these authors warn of the need to ensure that disruptive innovation includes profound changes in the educational model while improving the quality of learning and student achievement.

The disruptive responds to a transgressive and radical attitude (Olvera et al., 2023) that aims to improve educational processes, transform school life in a broad sense (Cortés et al., 2020), and promote transformative learning (Acaso et al., 2015), that is, to develop other ways of learning, other educational models (Valles-Baca and Acosta, 2022), and proposals to build other epistemologies. With this purpose on the horizon, disruptive processes link teaching and learning processes with the reality in which students are immersed (Johson, 2011) and aim to transform methodologies, school spaces, and classroom power hierarchies. Undoubtedly, we are dealing with a complex, systemic, and counter-hegemonic process that requires transformations of the educational context, didactic concepts, and educational objectives (Adell and Castañeda, 2012), which is a challenge and an opportunity.

In this regard, authors such as Fernández-Enguita (2018), Giroux (2011) and Rivas (2019, 2020, 2021) have argued that education systems are immersed in a neoliberal drift that leads them to develop educational practices that promote social reproduction, asymmetrical practices based on power relations, the homogenisation of processes, contexts and people, inequalities in access to education and the achievement of achievements and/or successes based on competitiveness, neglect and deterioration of community relations, the common good and the common good, homogenisation of processes, contexts and people, inequalities in access to education and achievement and/or success based on competitiveness, neglect and deterioration of community relations, the common good and natural spaces (Huerta-Charles and McLaren, 2021).

In the same vein, Mills (1997) argued at the time that educational practices reproduced oppressive power relations and were legitimised by the education system, which is why disruptive pedagogies are needed to challenge inequalities, dominant educational practices, and social injustice. As Pilonieta (2017) points out in this regard, it is about making education a politically “interesting” issue, which requires promoting distributed or horizontal leadership (Arribas and Torrego, 2007), promoting shared and participatory student responsibility, developing educational practices that facilitate research, reflection, application and dissemination of knowledge (Dede, 2007), and facilitating shared decision-making (Cortés et al., 2020).

In a particular way, disruption - pedagogical, innovative, or educational - refers to challenging school epistemologies (Anderson and Justice, 2015) and systems of value and knowledge that maintain conventional (Litts et al., 2020) and hierarchical ways of knowing and being (Litts et al., 2020). In this context, disruptiveness is accompanied by principles and strategies that invite us to discover and formulate new questions, build other resources and tools (Pilonieta, 2017), create languages and paths that invite circularity in educational and socio-affective relationships (Ahmed, 2018), personalise education, make educational resources more flexible in terms of time and place, and encourage active learning by seeking the interest and participation of students in their own learning, since, as pointed out by Valverde-Berrocoso et al. (2023), in secondary education, transmissive and unmotivating methodologies that exclusively promote memorisation are used to a large extent. In this sense, we present experiences, studies and research developed in secondary education that respond to the descriptors of disruptive innovation, disruptive pedagogy and/or disruptive education:

1) They are framed under the principles of critical pedagogy and have been the basis for a disruptive pedagogical practice.

2) They do not use technological tools.

2. METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

This paper presents a descriptive-retrospective systematic literature review (SLR) (Cuevas et al., 2022; Gabarda et al., 2022; Moriña et al., 2023), where the following stages have been considered: a) consider questions to analyse the studies; b) define the search strategy (descriptors, databases, etc.); c) apply the inclusion-exclusion criteria (IE); d) select the papers that respond to the research questions; and, e) analyse the information through a system of codes and categories.

The starting questions were: What are the theoretical references that underpin disruptive practices in secondary schools? What are these disruptive dynamics in secondary education and who do they affect? What are the most relevant and transformative contributions of international research on the implementation of disruptive pedagogies in secondary schools?

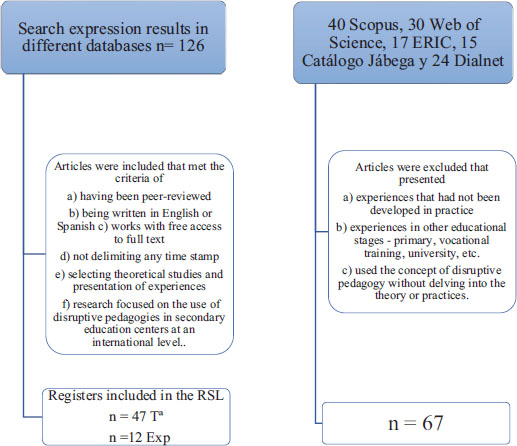

The selection of the scientific literature responds to an open practice in which research and works appearing in multiple databases have been considered: a) Scopus, currently considered a database with broad coverage in educational, social and humanistic studies (Marín-Suelves and Ramón-Llin, 2021; Torralbas et al., 2021); b) Web of Science; c) ERIC (Institute of Education Science); d) Jábega catalogue (University of Málaga library catalogue); and, e) Dialnet. The Boolean descriptors used were TITLE-ABS-KEY “Culturally-disruptive pedagogy” OR “Critical Pedagogy” AND “Secondary School”, AND “Disruptive pedagogy” OR “Disruptive Education” OR “Disruptive Innovation”. The search carried out in March 2023 yielded 126 results in the different databases (40 Scopus, 30 Web of Science, 17 ERIC, 15 Jábega Catalogue and 24 Dialnet).

Afterwards, they were distributed and the researchers carried out a subsequent ad hoc scrutiny. The inclusion criteria were: a) peer-reviewed; b) written in English or Spanish; c) works with free access to the full text; d) not limiting any time frame; e) selecting theoretical studies and presentation of experiences; and f) considering research focused on the use of disruptive pedagogies in secondary schools at a national and international level. The exclusion criteria were: a) research that used the concept of disruptive pedagogy but had not been implemented in practice; b) experiences in other educational stages - primary, Vocational Training (VET), University, etc.- as they did not fit the objectives of the aforementioned projects framing this work. The document selection process (Figure 1) was carried out in three stages:

FIGURE 1

FLOWCHART

Source: Own elaboration

1. A total of 126 articles were identified in the different databases.

2. Out of these articles, a total of 42 were excluded because they did not meet the above criteria.

3. Twenty-five articles were eliminated, considering, a posteriori, that these articles did not meet the criteria for research quality. This process left n = 47 - theoretical articles or theoretical conceptualisation articles - which allowed us to construct the theoretical framework and justify the article from a theoretical perspective, and n= 12 articles of national and international disruptive experiences in secondary education centres.

In this regard, the PRISMA, 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) standards (Page et al., 2021) were considered (Page et al., 2021), which resulted in the following flow chart (Prieto, 2020) (Figure 1).

In the last stage, and with the purpose of analysing and classifying the information through a system of codes and categories (Table 1), we have relied on the PICoS model (Participants, Topics of Interest, Context, Study Design) (González and Molero-Jurado, 2023) from which the different articles selected were subdivided and coded based on these and other variables that we consider of interest for the research such as: 1) questions on which this study was projected; 2) codes; and 3) categories of the same.

TABLE 1

QUESTIONS, CODES AND CATEGORIES

Categories |

Codes |

Descriptive data |

Country Year Data collection instruments Design Topics of interest |

Theoretical references |

Authors Theoretical foundations |

Pedagogical practices and who they affect |

Participants Context Experiences |

Relevant contributions |

Results |

Source: Own elaboration

2.1. Descriptive data

The reviewed documents present experiences developed in different settings: in rural schools (Ansell, 2002), in educational centres located in areas in need of social transformation (Alfrey and O’Connor, 2020; Cortés et al., 2020), with special education students in residential contexts (Alfandari and Tsoubaris, 2021), with Spanish students in secondary sducation centres (Di Stefano et al., 2021), with students in transition to post-secondary education (Luguetti et al., 2023), and in secondary schools with projects focused on the environment in Physical Education and Health (Alfrey and O’Connor, 2020; Warne et al., 2013), Religion (Hammer, 2023), Music and Visual Arts (Lousley, 1999; Ramos-Ramos, 2022).

The analysed studies were carried out in countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, Spain, and Zimbabwe. With regard to the instruments used to collect information, the main methodological tools used in the analysed studies were: interviews, focus groups, Theatre of the Oppressed, reflection and discussion groups, visual recording, use of photographs, photovoice, and document review.

3. RESULTS

The systematic review and the analysis of the selected texts address different aspects categorised in the following questions: 1) theoretical references of disruptive pedagogy as onto-epistemological sources on which certain educational practices are based; 2) pedagogical practices that promote disruptive dynamics and on whom these practices have an impact; and 3) relevant and transformative contributions on the implementation of disruptive pedagogy in educational centres.

3.1. Theoretical references of Disruptive Pedagogy

As Ibáñez (2016) points out, teaching in a disruptive way requires the use of flexible and diverse resources, both in terms of access and structure, to encourage cooperation between students. On the other hand, Ocaña-Fernández et al. (2020) point out that this way of teaching must favour processes of creativity and shared creation that promote processual evaluation, the social and meaningful construction of knowledge, commitment and motivation (Hedberg and Freebody, 2007).

For this reason, disruptiveness requires theoretical references that support the pedagogical approach, especially in such a vulnerable and changing stage as adolescence. At the secondary education stage, there is a need for actions that actively and participatively involve students, which implies breaking the hegemonic theoretical inertia in which a way of understanding the learning process is established. In this sense, the carried-out review points to the need to offer other epistemological references that address the keys to offering disruptive practices. These theoretical references address issues related to exclusion, poverty, gender, race, socio-political power structures, sustainability and ecology, cultural and linguistic heritage, dynamics of social and collective participation, and democracy. The identified references are the following:

- Paulo Freire’s contributions as a reference for the liberation and emancipation of people and collectives through education (Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1970) and its application in Boal’s work (2009) through the Theatre of the Oppressed.

- bell hooks (2021) known for her book Teaching to Transgress and for her contributions to feminist theory or Henry Giroux (2011) and Michael Foucault (1975) whose critical and reflective look on the educational system and social structures, as well as the promotion of social awareness and transformation are key to the construction of “another” school.

- From an environmental perspective, critical references such as David Orr (2002) promote ecological awareness and address the intersection between environment, sustainability, and ecological awareness as inherent principles of education.

- The feminist theories of Braidotti (2015) and the cultural studies of Ahmed (2018), broaden the educational scope towards a diverse and plural look at what it means to build citizenship, including the gender perspective in all educational issues. In this sense, one of the reviewed studies (Ansell, 2002) provides conceptual tools to analyse and question the social and cultural structures that perpetuate gender inequality in educational settings.

- The contributions of Alfandari and Tsoubaris (2021) question and challenge the foundations of existing educational structures, promoting the construction of new attitudes and behaviours in close interrelation between critical theory (Ball, 1994) and theories of social structures (Latour, 2007).

- Theories of power relations (Boal, 2009) and innovation, which are associated with emotional and social processes, are considered suitable theoretical foundations for addressing sensitive issues such as religious conceptions and their influence in educational contexts (Hammer, 2023).

- Finally, critical theories of art (Girault and Barthes, 2016) are presented as a valuable theoretical framework for addressing social and political issues in the field of education (Ramos-Ramos et al., 2022). The same is true of the epistemological approaches that underpin research linked to the field of health pedagogy in schools promoting disruptive dynamics (Warne et al., 2013). These critical theories applied to the art world have made it possible to explore and question artistic representations and their relationship with the dominant social and cultural structures, generating spaces for reflection and transformation in the educational sphere.

3.2. Pedagogical actions that promote disruptive dynamics and who they influence

Most of the pedagogical actions that are implemented in secondary schools and that are approached from a disruptive perspective arise as a response to tensions related to the curriculum and to structural, social, organisational, cultural, and neighbourhood issues, generally associated with depressed social contexts and vulnerable groups. The review shows a significant number of these pedagogical actions developed by teachers and which, at a methodological and strategic level, are presented under the umbrella of participatory action research (Hammer, 2023; Luguetti et al., 2023; Ramos-Ramos et al., 2022). These actions are as follows.

Alfandari and Tsoubaris (2021) and Hammer (2023) develop actions with interaction and role-playing dynamics in which students position themselves in different situations, assuming roles in a more empathetic and critical way towards different social situations. Alfandari and Tsoubaris (2021) propose a project with teachers at the Milestone Academy (United Kingdom) with the aim of seeking a scientific-critical education in various subjects, over ten classes lasting one hour each. The research used creative methodologies offering “alternative ground rules for communication”. They introduced body expression techniques, creative exchanges and body re-enactments based on the principles of the Theatre of the Oppressed and developed creative workshops to reflect on the project and its impact from the students’ experience. Hammer’s (2023) experience was also based on an action research project in a secondary school in Oslo (Norway). They used the basis of the Theatre of the Oppressed to work on concepts related to power, oppression, and empowerment in order to raise students’ awareness of social justice issues and the development of responsible and committed citizenship.

The research carried out by Cortés et al. (2020) presents the modifications to the curriculum by addressing structural and political issues of the school and how this has an impact on methodological and organisational dimensions. This study shows positive results of the implementation of a service-learning methodology in schools and how it generates spaces and times that favour collaborative work and the opening of the school to the community, giving rise to new relationships between social, educational, community, and business services.

The work of Luguetti et al. (2023) analyses how curricular transformation influences students’ future projections after completing secondary education and shows a programme designed collaboratively between students and teachers to improve the process of transition to post-secondary studies. This programme was designed under the theoretical premises of bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy (1994, 2003) and with the purpose of actively involving young people in developing strategies that would allow them to negotiate their future (life choices, studies, employment, etc.). The implementation of the programme allowed for an evaluation of the (co-)design and recommendations for the future. The process was recorded through recordings of group interviews and photographic records.

The introduction of critical pedagogy into the curriculum has also become commonplace within these disruptive practices. In this sense, teachers who adopt these references encounter barriers, resistance, and structural tensions when it comes to implementing these disruptive innovation projects. In this line, we highlight two projects developed in Zimbabwe; the first shows the effectiveness of enacting critical pedagogy within the curriculum of a Secondary School -Budirirai- in the Mwenezi district and in the subject of History during a regular academic year (Machingo, 2021). This project brought together six groups of learners (49 learners - 20 boys and 29 girls) from different villages (Musvoti, Zvihwa, Marufu, Sitera, Timire and Mangezi) with the aim of collaboratively showcasing the research that learners were doing by seeking and using primary sources for their learning and encouraging them to “feel comfortable critiquing their teacher and even textbooks” (Machingo, 2021, p. 6). As part of the research activities, students were encouraged to visit elders in the villages to obtain primary evidence and share their findings with their peers. This allowed them to critique the sources of the story and have meaningful interactions based on the reports of their peers. The second project presents a study conducted in the city of Lesotho (Ansell, 2002) and organised around two student focus groups. In these groups, opinions were raised and expressed and decisions were made on issues relating to rural secondary schools in Lesotho. These issues focused on the construction of gender identities among rural girls in the school context. The areas, with a highly gendered component, dealt with three axes that broke with the tradition of these towns: job prospects and paid work, domestic and reproductive work, and decision-making within the household.

Other research that addresses curriculum transformations are those carried out by Alfrey and O’Connor (2020), Warne et al. (2013), and Di Stefano et al. (2021), using the subject of Spanish language teaching. The research by Di Stefano et al. (2021) presents the implementation of certain activities in the classroom, such as: readings, multimedia texts, research journals, lecture or workshop materials, etc. The results suggest that such activities promote inclusion, cultural respect, equity, social justice, identification, and the challenge of eliminating stereotypes related to gender, race, language, immigration, and nationality in Spanish classrooms in the United States.

The case study presented by Alfrey and O’Connor (2020) shows a curriculum transformation project carried out in the Physical Education and Health department in an Australian high school in suburban Melbourne. The project uses an action research methodology, implemented each year in a different year group. Meetings were held with students and teachers involved in the subject and with other teachers who were not involved in the subject. At the end of each year, and with the feedback from a shared evaluation and feedback process, proposals for improvement were implemented in the following year.

The study presented by Warne et al. (2013) was conducted with a group of 35 students from an upper secondary school in the municipality of Östersund in northern Sweden. Students were selected according to their social position and the identification of young people at risk, and 5 teachers were selected too. All selected persons participated in 3 photovoice workshops with a duration of 120 minutes each. This methodology aims to increase the empowerment and participation of students in school dynamics. During the workshops, photographs and texts were used to explore relevant themes. The main findings were that low socio-economic status was associated with lower levels of mental well-being and lack of social capital was related to young people’s inability to participate in decision-making. However, at the same time, the student body came up with some salient proposals, such as: 1) more group work to improve classroom relationships; 2) provide teacher training to improve their pedagogical and leadership skills; 3) get more computers and repair broken ones to facilitate learning and reduce stress; 4) provide more tasty food in the school cafeteria to get energy for school work and wellbeing; 5) provide more food in the school cafeteria to get energy for school work and wellbeing; and 6) provide more food in the school cafeteria to get energy for school work and wellbeing.

Seeger et al.’s (2022) research, conducted in high-poverty high schools in the Washington D.C. metropolitan region, proposes dynamics in which students collaborate with teachers to restructure the educational curriculum, both in content and methodology. This approach is accompanied by readings of texts by Martin Luther King and presentations by Chimamanda Ndiche that address issues of equity and social justice, among others.

Also, the research by Ramos-Ramos et al. (2022) and Lousley (1999), focused on the curriculum of Music and Visual and Plastic Arts subjects, proposes to have an impact on the nearby social contexts with the aim of bringing about changes in the immediate context. The research by Ramos-Ramos et al. (2022) is located in the surroundings of a secondary school in the maritime district of Valencia with students in the 3rd year of Compulsory Secondary Education. The intervention is carried out through participatory action research in which students work with artists and educators to create artworks that address social and environmental issues. In Lousley’s (1999) research, based on critical ethnographic methodology and positioned within critical pedagogy, interventions were carried out in four environmental clubs in urban, multicultural high schools in the city of Metropolitan Toronto. This project conducted dialogues with all educational agents about culture, structures, relations, and discourses related to race, ethnicity, class and/or gender in order to understand and analyse how dominant environmental discourses are constructed.

3.3. Relevant and transformative contributions on the implementation of disruptive pedagogies in educational centres.

The consulted literature shows us successful experiences in terms of repercussions, transformations, and dynamics of change established in the educational centres in which they have been developed. The results presented by Alfandari and Tsoubaris (2021), Ansell (2002), Warne et al. (2013), and Hammer (2023) show that the use of critical pedagogies in the classroom has generated positive changes in the power relations between participants, both inside and outside the educational environment, contributing in an implicit and explicit way to the construction of a more democratic school and citizenship. In this sense, using theatre as a disruptive tool has allowed students the possibility of questioning their own ways of thinking, fostering change-oriented learning and generating modifications in the production of knowledge, as well as in the construction of subjectivities (Alfandari and Tsoubaris, 2021). In addition, students have improved their communication skills and their ability to resolve interpersonal conflicts, promote greater understanding, and accept diversity (Hammer, 2023); at the same time, teachers have positively valued their ability to act as facilitators (Warne et al., 2013).

Similarly, the study by Cortés et al. (2020) highlights that the implementation of disruptive pedagogies in schools has led to changes in teachers’ expectations by adopting a closer and more empathetic approach to students. There have also been transformations in the curriculum, which is beginning to be understood as a tool for transformation (Machingo, 2021) and not as a set of knowledge to be transmitted from a banking (Freire, 1970) and hierarchical conception. On the other hand, the studies by Alfrey and O’Connor (2020) and Luguetti et al. (2023) suggest that there is a change in the role of students, facilitating their active involvement through role-playing strategies, discussion groups, and debates. The use of these collaborative, participatory and reflective strategies generates critical awareness and drives proposals for curriculum modification based on theoretical and ideological foundations such as justice, social and educational engagement, critical perspective, connection of curriculum content to the real world and diversity of voices, as well as approaches that promote educational and social equity (Seeger, 2023).

4. CONCLUSIONS AND CHALLENGES

Just as the concept of ‘disruption’ is associated with innovation, it is difficult to address educational innovation without considering the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Learning and Knowledge Technologies (LKT), Technologies for Empowerment and Transformation (TEP) or Relationship, Information and Communication Technologies (RICT) (Del Río, 2023). In this regard, there are many authors who relate the concepts of disruptive innovation (Christensen, Raynor and McDonal, 2015; Pilonieta, 2017), disruptive pedagogy (Hedberg and Freebody, 2007; Ocaña-Fernández et al, 2020), and disruptive education (León, 2021; Molano, 2018) with the use of technologies; however, being aware that there are many educational practices that respond to their principles and do not use technologies and within the framework of the projects in which this research emerges, we propose the present study. In this sense, considering the work of Bower and Christensen (1995) as a starting point, we have shown that there are (n = 196) publications developed in secondary education that respond to the principles of disruptive innovation, disruptive pedagogy and/or disruptive education without making use of technologies. This poses a challenge, as well as a limitation, in the sense of knowing what other educational practices are developed under the terms disruptive innovation, disruptive pedagogy, and disruptive education and whether they respond to educational practices that break with hegemonic and traditional educational logics in terms of organisation, the implementation of methodologies, the structural and political aspects of the educational system, and the assumption or not of other pedagogical epistemologies. In spite of this, we can find other research and disruptive experiences that have not been considered because they do not use the search criteria used, which can be considered as another of the limitations of this study.

In order to address innovative and disruptive educational practices, the 12 analysed studies include so-called disruptive practices that have been characterised as: (1) counter-hegemonic educational experiences; (2) have transformed school cultures in their curricular, organisational, methodological and participatory dimensions; (3) have been developed without relying on the use of technologies; and (4) have been implemented in secondary education.

In a particular way, the analysis of these works shows us that disruptive pedagogies:

- transform contexts, settings, school roles, learning situations, and ways of teaching and learning.

- are based on co-responsibility, shared decision-making (Cortés et al., 2020), the search for social justice and the creation of constructive, dialogical and transformative educational relationships.

- improve school relations, coexistence and school climate (Cortés et al., 2020) and break with a school organisation that is based on a traditional school culture.

- are developed as attractive, stimulating, challenging, creative (Alliaud and Antelo, 2009), critical, and visibity-enhancing learning practices for students.

- generate learning that is connected to the reality and interests of the students (Johson, 2011)

- promote democratic educational processes (Fernández-Enguita, 2018; Rivas, 2021) that facilitate other forms of communication, relationships, and dialogue that are more horizontal, polyphonic and constructive.

This systematic review study shows another view of what for years we have considered as innovation, pedagogy, education and/or disruptive experiences; in this respect, the analysed studies present disruptiveness as an issue linked to educational processes and/or experiences where the educational community in general and the students in particular are co-participants and co-creators of teaching and learning processes, thus providing a more concrete and limited view of what this concept implies.

Similarly, we have been able to highlight that the use of educational strategies with a certain social background, such as the Theatre of the Oppressed, the use of participatory dialogue, dialogic gatherings, the creation of collaborative work groups, the development of transformative projects, participatory action research, artistic and musical creation, corporal expression, among others, must be incorporated more habitually into the educational sphere, as they favour expression and communication, reflection, the expression of social and educational justice, equity and social awareness, that is, they contribute to the personal transformation of students, and therefore, to community transformation.

Despite the complexity of addressing practices that respond to the principles of disruptive pedagogy, given the wide spectrum of practices that can be taken into account, it can be affirmed that these practices promote meaningful and self-regulated learning (Miralles et al., 2013). It places students at the centre of the learning process, increasing their protagonism as active agents (Cuetos-Revuelta et al., 2020) in an educational scenario that promotes critical reflection, autonomy, and creativity (Quiroz-Albán and Tubay-Zambrano, 2021). In light of these questions, is this not the school we want? This question challenges us in the search for a second challenge, that is, to build shared, democratic, constructive, dialogic educational processes that allow students to question and reflect on the hegemonic and neoliberal positions that dominate the educational, school, political, economic, and social space.

In this sense, we must consider some of the difficulties involved in introducing these disruptive practices in educational scenarios, either due to a lack of resources and support from institutional agents, or due to a lack of expectations regarding the projects being developed (Machingo, 2021), or due to friction and resistance on the part of teachers and students to the implementation of disruptive projects (Cortés et al., 2020). These aspects constitute limiting dimensions for the development of educational practices and strategies that attempt to carry out structural, organisational and/or educational transformation. At the same time, it is a complex challenge that requires disruptive, joint, shared, creative and democratic educational actions that are articulated in practice in educational responses that transcend the classroom, teachers, students, families, including social agents, and allow for the construction of a more critical, plural, civic, fair, tolerant, dialogic, and democratic citizenship.

REFERENCES

Abreu, J. M., & Lorenzo, H. D. R. (2020). Las potencialidades de la educación disruptiva en la formación de ingenieros en ciencias informáticas. UCE Ciencia. Revista de postgrado, 8(3), 1-12. https://uceciencia.edu.do/index.php/OJS/article/view/215

Acaso, M., Manzanera, P., & Piscitelli, A. (2015). Esto no es una clase: investigando la educación disruptiva en los contextos educativos formales. Ariel.

Adell, J., & Castañeda, L. (2012). Tecnologías emergentes, ¿pedagogías emergentes? En J. Hernández, M. Pennesi, D. Sobrino y A. Vázquez (Coords). Tendencias emergentes en educación con TIC. (pp. 18-63). Editorial espiral.

Ahmed, S. (2018). La política cultural de las emociones. UNAM.

Alfandari, N., & Tsoubaris, D. (2021). Temas controvertidos en la ciencia: Explorando las dinámicas de poder mediante la aplicación de pedagogías críticas en educación secundaria. Revista Izquierdas, 51, 1-18. https://www.izquierdas.cl/ediciones/2022/numero-51

Alfrey, L., & O’Connor, J. (2020). Critical pedagogy and curriculum transformation in Secondary Health and Physical Education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(3), 288-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1741536

Alliaude, A., & Antelo, E. (2009). Iniciarse a la docencia. Los gajes del oficio de enseñar. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 13(1), 89-100.

Al-Imarah, A., & Shields, R. (2019). MOOCs, disruptive innovation and the future of higher education: A conceptual analysis. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56(3), 258-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2018.1443828

Anderson, J. L., & Justice, J. E. (2015). Disruptive design in pre-service teacher education: uptake, participation, and resistance. Teaching Education, 26(4), 400–421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1034679

Ansell, N. (2002). ‘Of course, we must be equal, but …’: imagining gendered futures in two rural southern African secondary schools. Geoforum, 33, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-7185(01)00033-1

Arribas, J., & Torrego, J. (2007). El modelo integrado. Fundamentos, estructuras y su despliegue en la vida de los centros. En J. Torrego, J. Aguado, J. Arribas, J. Escaño, I. Fernández, S. Funes y M. Gil (Eds.), Modelo Integrado de Mejora de la Convivencia. Estrategias de mediación y tratamiento de conflictos (pp. 27-66). Graó.

Ball, S. J. (1994). Education reform: a critical and post structural approach. Open University Press.

Boal, A. (2009). Teatro del Oprimido. Alba Editorial.

Bower, J., & Christensen, C. (1995). Disruptive technologies: catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, 41–53. https://hbr.org/1995/01/disruptive-technologies-catching-the-wave

Braidotti, R. (2015). Lo Posthumano. Gedisa.

Christensen, C., Horn, M., & Johnson, C. (2008). Disrupting class: how disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns. McGraw-Hill.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail? Harvard Business School Press.

Christensen, C. M., Baumann, H., Ruggles, R., & Sadtler, T. M. (2006). Disruptive innovation for social change. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 94-101. https://hbr.org/2006/12/disruptive-innovation-for-social-change

Christensen, C. M., & Raynor, M. E. (2003). The innovator’s solution. Harvard Business School Press.

Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M., & McDonal, R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review, 93(12), 44–53. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

Cortés, P., Rivas, J. I., Márquez, M. J., & González, B. A. (2020). Resistencia contrahegemónica para la transformación escolar en el contexto neoliberal. El caso del instituto de educación secundaria Esmeralda en Andalucía. Izquierdas, 49, 2351-2377. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7633672

Cuetos-Revuelta, M. J., Grijalbo-Fernández, L., Argüeso-Vaca, E., Escamilla-Gómez, V., & Ballesteros-Gómez, R. (2020). Potencialidades de las TIC y su papel fomentando la creatividad: percepciones del profesorado. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.23.2.26247

Cuevas, N., Gabarda, C., Rodríguez, A., & Cívico, A. (2022). Tecnología y educación superior en tiempos de pandemia: revisión de la literatura. Hachetetepé. Revista científica en Educación y Comunicación, 24, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.25267/Hachetetepe.2022.i24.1105

Dede, C. (2007). Transforming Education for the 21st Century. Harvard Education Press.

Del Río, J. L. (2023). A vueltas con la llamada innovación educativa. Algunas reflexiones para suscitar el debate. Márgenes Revista De Educación De La Universidad De Málaga, 4(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v4i1.15923

Di Stefano, M., Almazán, A., Yepes, W., & Razifard, E. (2021). ‘Tu lucha es mi lucha’: teaching Spanish through an equity and social justice lens. Foreign language annals, 54(3), 753-775. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12578

Eyzaguirre, D. O. (2022). Educación disruptiva: nuevos desafíos en la formación de investigadores sociales en tiempos de Pandemia, y distanciamiento social. Revista Conrado, 18(89), 189-195. https://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado/article/view/2718

Fernández- Enguita, M. (2018). Más Escuela y menos Aula: la innovación en la perspectiva de un cambio de época. Morata.

Foucault, M. (1975). Vigilar y castigar: nacimiento de la prisión. Siglo XXI.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogía del oprimido. Siglo XXI.

Fullan, M. (2007). Change Theory as a Force for School Improvement. In Burger, J.M., Webber, C.F., Klinck, P. (Eds.), Intelligent Leadership. Studies in Educational Leadership (pp. 27-39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6022-9_3

Gabarda, V., Colomo, E., Ruiz, J. P., & Cívico, A. (2022). Aprendizagem de matemática aprimorada por tecnologia na Europa: uma revisão de literatura. Texto Livre, 15, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.35699/1983-3652.2022.40275

Girault, Y., & Barthes, A. (2016). Postures épistémologiques et cadres théoriques des principaux courants de l’éducation aux territoires. Education Relative à l’Environnement, 13(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.4000/ere.755

Giroux, H. A. (2011). On critical pedagogy. Continuum International Publishing Group.

González, A., & Molero-Jurado, M. del M. (2023). Relación existente entre creatividad y rendimiento académico en la adolescencia: Una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 10(2), 8. http://dspace.umh.es/handle/11000/29299

Hammer, A. (2023). Uso del teatro foro para abordar la homosexualidad como un tema controvertido en la educación religiosa. British Journal of Religious Education, 4(1), 23-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2021.2010652

Hedberg, J. G. (2011). Towards a disruptive pedagogy: changing classroom practice with technologies and digital content. Educational Media International, 48(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2011.549673

Hedberg, J., & Freebody, K. (2007). Towards a disruptive pedagogy: Classroom practices that combine interactive whiteboards with TLF digital content. University of Melbourne.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

Hooks, B. (2003). Comunidad de aprendizaje: Una pedagogía de la esperanza. Routledge.

Hooks, B. (2021). Enseñar a transgredir: La educación como práctica de la libertad. Capitán Swing Libros.

Huerta-Charles, L., & McLaren, P. (2021). Educar nuestra esperanza en tiempos de oscuridad: Cómo continuar trabajando hacia la justicia social en un mundo capitalista neoliberal. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 38, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2021.38.004

Ibañez, R. R. (2016). La innovación disruptiva y la formación de las competencias del siglo XXI en las universidades de América Latina. Adiós al modelo educativo dominante. TEXTOS. Revista Internacional de Aprendizaje y Cibersociedad, 20(1), 29-34. https://journals.eagora.org/revCIBER/article/view/187

Johson, C. (2011). La manera disruptiva de aprender. Redes, 3 julio. http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/redes/redes-entrevista-curtis-johnson-asesoreducativo/1144909/

Latour, B. (2007). Nunca fuimos modernos. Siglo XXI.

León, C. M. (2021). Modelos disruptivos e innovadores: una respuesta desde la educación superior a la pandemia del COVID-19. Sapientia Technological, 2(1), 11-21. https://sapientiatechnological.aitec.edu.ec/index.php/rst/article/view/7

Litts, B. K., Tehee, M., Jenkins, J., Baggaley, S., Isaacs, D., Hamilton, M. M., & Yan, L. (2020). Culturally disruptive research: A critical (re) engagement with research processes and teaching practices. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(9/10), 769-784.

Lousley, C. H. (1999). (De)Politicizing the Environment Club: environmental discourses and the culture of schooling. Environmental Education Research, 5(3), 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462990050304

Luguetti, C., Ryan, J., Eckersley, B., Howard, A., Buck, S., Osman, A., Hansen, CH., Galati, P., Cahill, R. J., Craig, S., & Brown, C. (2023). ‘It wasn’t adults and young people […] we’re all in it together’: co-designing a post-secondary transition program through youth participatory action research. Educational Action Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2023.2203408

Machingo, P. (2021) Experiences of enacting critical secondary school history pedagogy in rural Zimbabwe. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 9(1), 2010927. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2021.2010927

Marín-Suelves, D. & Ramón-Llin, J. (2021). Physical Education and Inclusion: a Bibliometric Study. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 143, 17-26. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/1).143.03

McDonald, R., & Eisenhardt, K. (2017). Parallel Play: Startups, Nascent Markets, and the Search for a Viable Business Model. Working Paper (14-88). Harvard Business School.

Mills, C. (1997). The racial contract. Cornell University Press.

Miralles, P., Gómez, C. J., & Arias, L. (2013). La enseñanza de las ciencias sociales y el tratamiento de la información. Una experiencia con el uso de webquests en la formación del profesorado de educación primaria. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 10(2), 98-111. https://rusc.uoc.edu/rusc/es/index.php/rusc/article/view/v10n2-miralles-gomez-arias.html

Molano, M. (2018). Educación disruptiva en el contexto lasallista: glosas para la discusión. Revista de la Universidad de La Salle, 75(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.19052/ruls.vol1.iss75.4

Moriña, A., Carballo, R., & Castellano-Beltran, A. (2023). A Systematic Review of the Benefits and Challenges of Technologies for the Learning of University Students with Disabilities. Journal of Special Education Technology, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/01626434231175357

Ocaña-Fernández, A., Montes-Rodríguez, R., y Reyes-López, M. L. (2020). Creación musical colectiva: análisis de prácticas pedagógicas disruptivas en Educación Superior. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 17, 3-12. https://doi.org/10.5209/reciem.67172

Olvera, J., Montes, R., & Ocaña, A. (2023). Innovative and disruptive pedagogies in music education: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Music Education, 41(1). 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614221093709

Orr, D.W. (2002). The nature of design: ecology, culture, and human intention. Oxford University Press.

Ortega, V. S., & Llach, M. C. (2016). Pedagogías disruptivas para la formación inicial de profesorado: usando blogs como e-portafolio. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 20(2), 382-398. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56746946021

Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., & Moher D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International journal of surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Pilonieta, G. (2017). Innovación disruptiva. Esperanza para la educación de futuro. Educación y ciudad, 32, 53-64. https://doi.org/10.36737/01230425.v0.n32.2017.1627

Prieto, J. M. (2020). Una revisión sistemática sobre gamificación, motivación y aprendizaje en universitarios. Teoría De La Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 32(1), 73-99. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.20625

Qiroz-Albán, A. T., & Tubay-Zambrano, F. (2021). Las TIC´ s como teoría y herramienta transversal en la educación. Perspectivas y realidades. Polo del Conocimiento, 6(1), 156-186. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v6i1.2130

Quilty, A. (2017). Queer provocations! Exploring queerly informed disruptive pedagogies within feminist community-higher-education landscapes. Irish Educational Studies 36(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2017.1289704

Ramos-Ramos, P., Gómez Colchero, E., Bort Calvo, V., & García García, F. (2022). Belleza degradada: arte contextual y educación en el paisaje a través de un proyecto en educación secundaria. ARTSEDUCA, 32, 107-120. https://doi.org/10.6035/artseduca.6128

Rivas, J. I. (2019). Re-instituyendo la investigación como transformadora. Descolonizar la investigación educativa. En A. De Melo, I. Espinosa, L. Pons y J. I. Rivas (Coords.). Perspectivas decoloniales sobre la educación, (pp. 23-60). Unicentro/UMA Editorial.

Rivas, J. I. (2020). La investigación educativa hoy: del rol forense a la transformación social. Márgenes, Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 1(1), 3-22. http://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v1i1.7413

Rivas, J. I. (2021). Cambiando de paradigma. Otra investigación necesaria para otra educación necesaria. En E. López (Comp. y Ed.), Círculos Pedagógicos. Espacios y tiempos de emancipación (pp. 177-182). Nueva Mirada Ediciones.

Seeger, M. T. (2023). Becoming a Knower: Fabricating Knowing Through Coaction. Social Epistemology, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2023.2266716

Seeger, C., Parsons, S., & View, J. L. (2022). Equity-Centered Instructional Adaptations in High-Poverty Schools. Education and Urban Society, 54(9), 1027-1051. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245221076088

Torralbas, J. E., Batista, P., Herreros, A. L., & Carballo, A. A. (2021). Procesos de cohesión grupal e inclusión educativa. estudio bibliométrico en la base de datos Web of Science. Revista Cubana de Psicología, 3(3), 27-40. https://revistas.uh.cu/psicocuba/article/view/199

Valles-Baca, H. G., & Acosta, H. P. (2022). La educación disruptiva y el desarrollo de competencias universitarias. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 13(25). https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v13i25.1284

Valverde-Berrocoso J., Rivas-Flores J. I., Anguita-Martínez R., & Montes-Rodríguez, R. (2023). Pedagogical change and innovation culture in secondary education: a Delphi study. Front. Educ., 8, 1092793. https://doi:10.3389/feduc.2023.1092793

Vratulis, V., Clarke, T., Hoban, G., & Erickson, G. (2011). Additive and disruptive pedagogies: The use of slowmation as an example of digital technology implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(8), 1179-1188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.06.004

Warne, M., Snyder, K., & Gillander, K. (2013). Photovoice: an opportunity and challenge for students’ genuine participation. Health Promot Int., 28(3), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/das011